“I want future generations to know that we are a

people who see our differences as a

great gift, that we are a people who value the dignity and worth of every

citizen – man and woman, young and old,

black and white, Latino and Asian, immigrant and Native American, gay and

straight, Americans with mental illness

or physical disability.”

-- U.S.

This month’s 25th anniversary of Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA

In

Andy Imparato’s blog post, The ADA and Claiming Disability, I thought about inserting “old age” for

“disabilities”:

“Rather

than buying into the larger societal narrative that disabilities are inherently

limiting, we have an opportunity to recognize that personal experience with

disability can lead to greater personal strength, creative problem-solving, and

a stronger connection to other populations who face discrimination at work, at

school and in the community.”

From ugly to beautiful law

In 1867, the first “ugly law,” making it illegal

for persons with disabilities to appear in public, was enacted in San Francisco

Carla Johnson of San Francisco Mayor’s Office on Disability (MOD) and Community Alliance for Disability Advocates (AIDS Legal Referral Panel, Senior and Disability Action, San Francisco

IHSS Public Authority,

The Arc of San Francisco,

LightHouse for the Blind,

Independent Living Resource Center of San Francisco, Paul K. Longmore Institute on Disability, Community Living Campaign,

Toolworks, Bakeworks) hosted ADA Month Kick Off Celebration on July 1st inside City Hall (which celebrated its own centennial

last month).

Mayor Ed Lee greeted the audience of “beautiful

people” and praised ADA for promoting independence,

inclusion and community, consistent with making San Francisco San Francisco ,

he introduced a resolution that was adopted nationwide to recommit

cities to the goals and ideals of ADA San Francisco

District

1 Supervisor Eric Mar honored grassroots organizations like ILRC and

co-sponsors for organizing California San Francisco

Kathy Martinez, a former ten-year-old actress in Lassie TV show, recalled being age 17

during 1977 sit-in that was an “invitation to fight for our civil rights.” As former Assistant Secretary in Office of Disability Employment Policy at U.S. Department of Labor, she advocated hiring people with disabilities to

achieve financial independence.

Former Assemblymember Tom Ammiano recalled being

a school teacher who brought his hungry students to the 504 rally, so when

asked, “What do we want?” they replied, “French toast,” instead of “civil

rights!” On a more serious note, he

reminded us that we all get old, when accommodations are welcome then, but

awareness is needed beforehand to prepare. He said

to look for the 2016 ballot measure for Dignity Fund,

which would allocate real estate taxes for seniors and persons with

disabilities.

Access SFUSD appeared on stage twice: to speak on disability perspectives (“because of ADA

San

Francisco MOD squad, established in 1998 as the City's overall ADA Coordinator, and banner reminded us that celebrating 25 years of ADA doesn't stop here: the struggle continues to eliminate attitudinal, communication, transportation, policy and physical barriers in order to achieve full integration of people with disabilities in our society.

Ms.

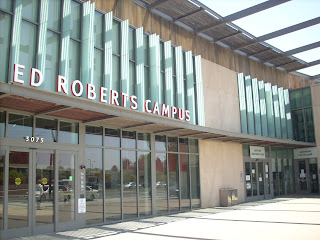

Wheelchair California at Patient No More panel, a preview of

larger exhibit at Ed Roberts Campus in Berkeley

Universal design

Panelists discussed ADA ’s impact on design with architect Michael Chambers as moderator at SmithGroupJJR in San Francisco

·

Architect Chris

Downey of Architecture for the Blind:

ADA

·

Disability Rights Advocates attorney Zoe Chernicoff:

ADA

·

Architect and

gerontologist Alexis Denton:

ADA

·

Architect Gilda

Puente-Peters: ADA model has been used

internationally by other countries to develop their own access standards, but ADA

·

Center for

Independent Living’s work and benefits counselor Alana Theriault: ADA

Chris and Alana mentioned Berkeley

Ed

Roberts Campus housed the equally accessible exhibit,

Patient No More! People with Disabilities Securing Civil Rights,

which held its grand opening on ADA

Spiral ramp inside Ed

Roberts Campus

Quiet area outdoors to

get away from sensory overload

Disability Mural (2000-Present) is the first community artwork about the everyday experiences of

living with a disability, created by people with and without disabilities.

Mural tile reads: "One day many people will learn to sign, and we all be seeing voices...when all the world speaks with its hands!"

Mural tile reads: "One day many people will learn to sign, and we all be seeing voices...when all the world speaks with its hands!"

Room for improvement on one

size fits all

Rosemarie Garland-Thomson has noted that disability is the body's response over time to its environment. Temporarily

abled people who acquire a disability later in life experience disability differently (like learning a foreign language later in life),

than people who have a congenital disability and already have adapted to “fit

in” the built environment or changed the inaccessible environment to accommodate their individual differences (latter often benefits our broader society). People with a congenital disability do not experience loss over not being able to do “normal” activities because they

never did, so this self-acceptance reframes “the problem is the solution.”

Celebrating disability civil rights

Cathy Kudlick, who developed

Patient No More exhibit with her team

at Longmore Institute, welcomed attendees at grand opening.

“Civil Rights were knocking at our door,

But

Carter wouldn’t stand on 504…

After

four years of delay,

We

came to claim the ground we’d gained…

Well,

for 28 days unafraid

150

people with disabilities they stayed.

They

had their eye on the prize. They held

on.

Hold

on. Hold on.

Keep

our eyes on the prize. Hold on…”

Dennis Billups,

504 Chief Morale Officer, led chant, “1-2-5-0-4. Kickin’ in the bathroom door

…We’re rolling in victory now.”

Interactive exhibit,

with poster of Billups during 504 demonstration, invited visitors to respond,

What makes you “patient no more”?

Bruce Oka, 504

participant and former SFMTA Director,

said he was "patient no more" because he was tired of being excluded, and talked

about need to be included.

Corbett O’Toole said she

was "patient no more" because there are only two lawyers in the nation available

to represent parents with disabilities losing custody of their children.

Persons with

disabilities nationwide occupied the regional offices of HEW in April 1977, but

only San Francisco

·

504

protests and ADA legislation grouped people with

many different disabilities together,

so there would be one big ADA

·

504

resulted in a national disability rights

movement and national disability organizations that could promote and defend

ADA

·

504

defined disability flexibly and took

prejudice into account, so ADA

Section 504 served as a

template for the more comprehensive ADA

Becoming Real in 24 Days: One Participant’s Story of the 1977 504 Demonstrations author and 504 participant HolLynn D'Lil.

disability = diversity

Invisible disabilities

At

this month’s Mayor’s Disability Council meeting,

attendees presented on “what ADA

means to me” with several mentioning “invisible” disabilities (like learning differences and

psychiatric disorders), how physical and mental disabilities influence another,

and the financial impacts. The majority

of disabilities are non-apparent, and until ADA Amendments Act of 2008,

the U.S. Supreme Court did not consider persons with diabetes and mental

illness as disabled, and thus not entitled to protection against discrimination. In fact, neuropsychiatric disorders represent

the largest category of disability in the U.S.

People

With Disabilities Foundation (PWDF),

a non-profit that aims to “provide total integration

of people with mental disabilities into the whole of society,” hosted a delegation of disability advocates from 20

countries, at the invitation of U.S. Department of State’s International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP), Access for All: Enhancing the Lives of

People with Disabilities. Founded 15 years ago

in San Francisco, PWDF won the nation’s first court case

requiring a federal agency to accommodate the needs of persons with mental disabilities, who were denied equal access to Social Security disability

programs, in violation of Section 504 of the Rehab Act of 1973,

because they could not understand the complex eligibility rules. PWDF’s Parity in Advocacy initiative works to provide equal access to legal representation for those with mental

disabilities (advocacy version of Mental Health Parity).

With the passage of ADA 25 years ago, the U.S.

became the first country in the world to adopt national civil rights legislation

banning discrimination against persons with disabilities. ADA was the model for the Convention on the Rights

of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), which U.S. President Barack Obama signed

in 2009,

but its ratification voted down by the Senate.

The

50th anniversary of Older Americans Act (OAA) on July 14 was a non-event in the Bay Area. The decennial White House Conference on Aging (WHCoA) took place the day before with at least one

watch party of the live stream in San Francisco

Senior

and Disability Action’s monthly meeting celebrated

I was

not aware of any delegations visiting from other countries to learn about OAA

as a model . . .

Model

garden at 30th Street

Health Care for Americans with Disabilities — 25 Years after the ADA

ReplyDeleteGeorgina Peacock, M.D., M.P.H., Lisa I. Iezzoni, M.D., and Thomas R. Harkin, J.D.

July 30, 2015DOI: 10.1056/NEJMp1508854

… substantial disparities remain in areas of employment, earned income, access to the Internet, transportation, housing, and educational attainment. Each of these disparities contributes to poorer health for this segment of our population. The recent Affordable Care Act (ACA) may help improve access to health care for people with disabilities, but the persistence of health disparities and barriers to health care indicates that more remains to be done.

Approximately 56.7 million Americans live with disabilities, with rates ranging from 8.4% among children under 15 years of age to 70.5% among adults over 80 years of age. Over our life spans, most of us will acquire disabilities. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently reported that among U.S. adults living in community settings, 22% have a disability, …Given the increasing prevalence of diabetes, arthritis, and other chronic conditions, new interventions for extremely premature infants, and increased life expectancies for people with congenital conditions (e.g., spina bifida and congenital heart defects), the number of Americans with disabilities in all age groups is likely to increase.

Healthy People 2020, which set national health priorities for 2010 to 2020, documented that people with disabilities were more likely than those without disabilities to experience difficulties or delays in getting health care they need, not have had a mammogram in the past 2 years, not have had a Pap test within the past 3 years, not have had an annual dental visit, not engage in fitness activities, use tobacco, be overweight or obese, have high blood pressure, and experience symptoms of psychological distress…

Many factors may contribute to these disparities, including physical barriers to care (e.g., inaccessible medical diagnostic equipment such as examination tables, weight scales, and imaging technologies); noninclusive health or wellness programs designed for people without disabilities; transportation problems, especially in areas with poor public transportation; inaccurate or inadequate knowledge or stigmatizing attitudes of clinicians about disabling conditions; competing priorities in the health care system; prior difficult or unpleasant experiences getting health care; and communication barriers, such as failure to accommodate deaf patients who require sign-language interpreters. The effects vary depending on the disability type: stigma, for instance, is especially problematic for people with mental health or intellectual disabilities, whereas inaccessible equipment can prevent someone with significant mobility disability from obtaining even basic services (e.g., getting weighed).

Recognizing persisting health and health care disparities, lawmakers inserted provisions related to disability into the ACA….

To enhance public health surveillance and monitor interventions, Section 4302 calls for gathering systematic and consistent data on populations affected by health disparities, including people with disabilities. Section 5307 authorizes federal funding for training health care professionals in competencies related to “disability culture” and development of model curricula on the needs of people with disabilities. Of critical importance, for example, is training in the cervical- and breast-cancer screening needs of women with physical, intellectual, or mental disabilities.

Section 4203 of the ACA calls for the “establishment of standards for accessible medical diagnostic equipment”;…

http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1508854

A Disabled Life Is a Life Worth Living

ReplyDeleteBen Mattlin

OCT. 5, 2016

…It’s not generally acceptable in my segment of the disability community to harp on our defenselessness. Rather, the idea is to assert core competencies, to distance ourselves from the Jerry’s Kids’ model and anything else remotely pitiful. We seek fair treatment, rightful access to everything in society …Highlighting the downside of disabilities seems counterproductive and self-pitying.

But the truth is, to live with a disability is to know an abiding sense of fragility. That isn’t always easy, but it’s not necessarily all bad either.

I decided long ago that if I’m going to like myself, I have to like the disability that has contributed to who I am. Today, my encroaching decrepitude is frequently a source of emotional strength, a motivator to keep fighting, to exercise my full abilities in whatever way possible. Let’s face it, people with disabilities are nothing if not first-class problem-solvers. We find all manner of devices to enable us…

True, it is a hassle having to devise alternative methods for living a normal life. But when it works, Oh, how good it feels! How triumphant and liberating! I’m proud of my persistence and creative coping skills.

Of course at times I grow despondent. I fall into what I call “useless cripple syndrome.” Most of my able-bodied contemporaries are at the pinnacle of their careers, and I’m just getting by. I shouldn’t complain, I tell myself. Unemployment among disabled people is crushingly high.

Because of this, I feel positively driven to make good use of every day that I’m not stuck in bed with a respiratory infection or other ailment. Yes, that may make me an overachiever…The point is, I want to accomplish everything I can while I still have the ability. I may feel fine today, but I can’t count on tomorrow — or even an hour from now. I’ve seen too many friends in the disability community perish too young.

…14-year-old Wisconsin girl with S.M.A., Jerika Bolen, who was planning to end her own life by refusing life-sustaining treatment. Just a few weeks ago, she did, and died.

…Growing up with a disability, I often became isolated. Feeling devalued by my peers, with no confidence in my future, I experienced intermittent but profound depression…As disabled people, we are endlessly buffeted by circumstances beyond our control.

I dare not judge Jerika Bolen. I don’t know the entirety of her situation. But I do wish she had found the will to live. I’m saddened — as were many others with S.M.A, and some disability rights groups — to think others might grow so weary or apprehensive that they follow her example. I hope she received the same level of intervention any other suicidal 14-year-old would. I wish I could have told her about the psychological alchemy that can turn frustration into an internal fuel. If I’d had the chance I would have told her that society needs its disabled people, too.

The perseverance to live fully with a profound disability comes, I think, in part from honestly facing your own powerlessness and frailty, and recognizing how much worse things have been and could still be. This can instill a delight in the now. In living with a disability, you’ve already dealt with much of what other people fear most, and if you come out on the other side you are, by definition, a survivor. The resolve required, and begrudging acceptance of what you can’t change, may bring a kind of wisdom.COMMENTS

I realize that external conditions can make all the difference. My family has given me unflagging support. My parents fought to get me integrated into regular schools, long before it was mandated, and insisted I could become anything …

I wish I could have persuaded Jerika Bolen and others like her to keep striving to do the same…

I wish I could have convinced her that she wasn’t better off dead than disabled.

Ben Mattlin is the author of the memoir “Miracle Boy Grows Up.”

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/05/opinion/a-disabled-life-is-a-life-worth-living.html

Incentives offered by ADA should be everyone’s concern

ReplyDeleteBy Jessie Lorenz on April 18, 2018 1:00 am

…The ADA requires things like curb cuts on city streets to increase access for people who use wheelchairs. It is incidental, though not insignificant, that people who use baby strollers and rolling suitcases also benefit from them. In a world often described in “us” and “them” terms, the reality is much more complex than that. The requirements of the ADA always have always lead to innovation, and, in truth, the benefits of increased accessibility improve lives across the board.

Back in 2006, when blind groups were telling Steve Jobs the iPhone was not accessible, Jobs, as many in the business world are wont to do, replied that the iPhone was a “purely visual device” and that blind users should instead have their own developers work on a phone for exclusively for them. That could’ve been the end of the story if it weren’t for the ADA.

Instead, the government was able to force the hand of the developers at Apple to get creative. That’s because the ADA stipulates educational institutions must utilize accessible technologies. The “carrot and the stick” that the government had at its disposal, via the ADA, lead to an accessible iPhone after all. The first talking computer and optical recognition software was created with blind users in mind. These are now regular features in the smart phones we rely on.

As a blind person who travels a lot, Google Glass’ new technology, Aira, has been a game-changer for me. Aira connects to a human who can give visual interpretation within 10 seconds, and airports are now paying for this service instead of having an assistant guide me around. This is a liberating and dignifying use of technology.

Artificial intelligence is going to change the world for everyone. But in some cases, it can completely mitigate a disability. And in a world where age-related vision loss is something that will effect nearly everyone who lives long enough, the incentives offered by the ADA toward accessibility should really be everyone’s concern.

…Disability rights is …about making sure the doors of equality are open to everyone so that folks with disabilities, who don’t want to be relegated to a life on the dole, have access to authentic opportunities to not only find work but to live the American Dream.

Jessie Lorenz is executive director of the Independent Living Resource Center San Francisco.

http://www.sfexaminer.com/incentives-offered-ada-everyones-concern/

A Milestone for Community Living: Reflecting on 19 Years of Olmstead

ReplyDeleteBy Lance Robertson, ACL Administrator and Assistant Secretary for Aging

The right to live independently, integrated into the community, is a cornerstone of the disability rights movement. It’s also the core of the mission for the Administration for Community Living — it’s even built into our name. ACL was created around the fundamental principle that all people, regardless of age or disability, should be able to live independently and fully participate in their communities.

For decades, people with disabilities have worked to turn this principle into a reality. Looking at this history, certain moments stand out as turning points. For example, the passage and implementation of landmark legislation including the Americans with Disabilities Act, Rehabilitation Act, Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, and Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act have each helped make community living possible for more Americans.

Today, we celebrate the anniversary of another important milestone. Nineteen years ago, the Supreme Court ruled in Olmstead v L.C. that people with disabilities cannot be unnecessarily segregated into institutions (like nursing homes and other facilities) and must receive services in the most integrated setting possible.

The Olmstead decision opened the door to innovations and programs that make services and supports more available, allowing people to live the lives they choose, in the communities they choose, with family and friends. It also has given the aging and disability networks a new tool to advance community living. I am proud of the work ACL, the predecessor organizations it brought together in 2012, and the many organizations we fund have done to fulfill Olmstead’s promise and make a difference in peoples’ lives…

People of all ages have benefited from Olmstead. ACL’s programs for older adults are doing their part to make community living possible by providing critical services, including meals and caregiver support.

ACL, our networks, and partners are demonstrating that expanding community living options is both the right thing to do and it’s often the fiscally responsible thing to do. Skilled nursing and residential living can cost upwards of $225,000 a year. Services and supports provided in the community are usually far less expensive. The potential for cost savings can be seen in a demonstration program known as Money Follows the Person (MFP). The program eliminates barriers to home- and community-based services and allows people to transition out of institutional settings and receive long-term services and supports at home. A report released by HHS in December looking at eight years of MFP data estimated that, in the first year after transitioning into the community, MFP participants saved Medicaid and Medicare $978 million in medical and long-term support and services costs.

We’ve come a long way since the Olmstead decision, but we’re far from done. As important as our successes are—especially to the people who now live independently in communities—we still have a lot of work to do to make the vision of Olmstead and the Americans with Disabilities Act a reality.

ACL is committed to seeing community living become a reality for every older adult and person with a disability who seeks it.

I’m honored to work with you towards this important goal.

After all, while the Olmstead decision may have particular significance for older adults and people with disabilities, ultimately, it benefits all of us. Our communities and our lives are richer with a diversity of people, abilities, and perspectives. Older adults offer a critical link to our history and culture in our neighborhoods, congregations, and gatherings. People with different life experiences advance new ideas and spark innovation in business and the community.

We all miss out when community living is out of reach.

http://www.ilru.org/news/milestone-for-community-living-reflecting-19-years-olmstead

Community Living for All: A Celebration of the Americans with Disabilities Act

ReplyDeleteBy ACL Administrator Lance Robertson

Today we celebrate another historical moment for independence. On this day in 1990, President Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act, which affirms those rights for people with disabilities and significantly expanded their opportunities for independence.

One of our country’s most comprehensive pieces of civil rights legislation, the ADA prohibits discrimination on the basis of disability and establishes that people with disabilities have the right to the same opportunities as people without disabilities. It ensures access to public spaces, transportation, employment, and countless other things that most of us take for granted. Its fundamental purpose is the integration of people with disabilities into the mainstream of American life.

We still have work to do, but the ADA, together with legislation like the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, has changed our world. Curb cuts are now so common that many younger people have no idea they originally were created to make sidewalks accessible for people with disabilities. Innovations and new developments in assistive technology have exponentially increased access to workplaces, entertainment, and self-sufficiency. Special education is now a service, not a place, and children are growing up with the realization that disability is a normal part of life.

Because of these advances, and many others like them, people with and without disabilities increasingly live, work and play side by side. A generation after the ADA, community living is the expectation for all people, regardless of age or disability.

That is not only good for people with disabilities. It is good for all of us. The strongest and most vibrant communities include people of all ages and abilities, each adding their voice, perspective and talents. We all benefit when everyone can contribute to their full abilities, work and grow the economy, and actively participate in community activities.

The Administration for Community Living was created around the fundamental principle that older adults and people of all ages with disabilities should be able to live where they choose, with the people they choose and with the ability to participate fully in their communities. By funding services and supports provided by networks of community-based organizations, and with investments in research and innovation, ACL helps make this principle a reality for millions of Americans.

At ACL:

• We believe community living should always be the expectation.

• “Community” means places where people of all ages, with and without disabilities, live, grow, learn, work, are valued and create a better shared future together.

• We are committed to upholding the rights guaranteed in the Americans with Disabilities Act and reinforced through the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Olmstead v. L.C. – a decision we fully support.

• We are firmly committed to supporting the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in implementing the federal home- and community-based settings rule.

• In short, at ACL, we are fully committed to making community living possible for all.

We are proud of the work that has been done, and we celebrate the gains achieved since the ADA was passed. That progress fuels our passion for our work.

As we celebrate the 28th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act, we also confirm our commitment to working with people of all ages with disabilities, our grantees and other disability advocates, and partners across government, industry, academia, and communities to improve the availability and quality of the services and supports people need to live in their communities. Working together, we can fully realize the promise of the ADA.

https://www.acl.gov/news-and-events/acl-blog/community-living-all-celebration-americans-disabilities-act

Celebrating 50 Years of the Architectural Barriers Act

ReplyDeleteSeptember 7, 2018

Lance Robertson, ACL Administrator and Assistant Secretary for Aging

As chair of the U.S. Access Board, I had the privilege of participating in an event today celebrating the anniversary of the Architectural Barriers Act (ABA) of 1968 and the fifty years of progress it helped spark.

Before the ABA was passed, accessibility standards were often inconsistent -- and just as often ignored. The American National Standards Institute developed the first accessibility standards in 1961 with the help of Easter Seals and the research of the University of Illinois. Many states used these early standards to develop accessibility requirements in their building codes. However, other states adopted access requirements that ranged from lax to nearly nonexistent. This resulted in great discrepancies in accessible design requirements from state to state, and in some cases, from city to city.

This had real life impacts. It meant that a wheelchair user could easily go to the post office in one town but not in a nearby state or community. The same problem existed with respect to sidewalks, entrances, bathroom stalls, paths of travel, signage, and everything else that makes a building accessible.

The Architectural Barriers Act helped solve this problem by creating a mechanism for developing and setting clear and consistent nationwide accessibility guidelines for the federal government. It literally began to open the doors of government to Americans with disabilities like never before by requiring buildings constructed or renovated with federal funds, as well as those owned or leased by the federal government, to be accessible and usable by people with disabilities. For the first time, schools, housing, offices, courts, hospitals, stadiums, post offices, and countless other facilities were available to people with disabilities.

This did far more than eliminate physical barriers. It helped level the playing field by promoting greater access and equal opportunity to public education, colleges and universities, community living, employment, health care, and more. In this way, the ABA helped pave the way for the last five decades of civil rights advances for Americans of all ages with disabilities.

One of the law’s lasting legacies is the innovation in design and technology it helped spur across the private, public, and nonprofit sectors. Over the years, the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR) and the Access Board – together with many other federal agencies – have invested significant resources, time, ingenuity, and rigor in generating and effectively sharing new knowledge to improve the opportunity and ability of individuals with disabilities to access the built environment, technology, and the digital world. The quest continues and so does the return on investment.

We at ACL are especially proud of the important role the Access Board and NIDILRR have played in advancing the science, discipline, and esthetic of what we now call universal design. Universal design uses a broad-spectrum of ideas and methods to design and develop buildings, products, and environments that are inherently accessible to all people of all ages and abilities.

As he was signing the landmark Americans with Disabilities Act into law in 1990, President George H.W. Bush said the law would take a sledgehammer to the shameful wall of exclusion that has prevented far too many with disabilities from exercising their full rights and responsibilities. It is important to recognize and celebrate that the first blow against this wall was struck by the Architectural Barriers Act and those that made it possible.

We are a better nation and a better people because of it, and we remain committed to advancing the principles behind it.

https://www.acl.gov/node/2006/