·

In

USA, 1 in 7 people is a caregiver and more than 2/3 of people will need assistance

with daily tasks as they age.

·

In

USA, more than 53 million family caregivers provide approximately $470 billion

in unpaid support annually for their loved ones to be able to live in their

communities.

·

Family

caregivers often provide support without a formal assessment of their needs or

of the person receiving support; learn “on the job,” taking on complex medical,

administrative and care coordination activities.

·

Lost

income due to family caregiving is estimated at $522 billion each year.

Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregivers’ Working While Caring: A National Survey of Caregiver Stress in the U.S. Workforce (Sep. 28, 2021) found that 1 in 5 full-time workers care for a family member with a serious illness/disability; nearly 20% of them quit a job to care for a relative, while 44% switched to part-time work. Rosalynn Carter has advocated for establishment of a new Office of Caregiver Health, within the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, intended to improve coordination within the bureaucracy.

My

Administration is committed to strengthening American families and easing the

burdens of caregiving. That is why my American

Rescue Plan provided an additional $145 million in funding for the National

Family Caregiver Support Program,…also provided States with additional Medicaid

funding to strengthen and enhance their home- and community-based services

(HCBS) program. My Administration’s Build

Back Better agenda will build on this down payment by continuing to invest

in the caregiving infrastructure for HCBS and increasing pay and benefits to

address the direct care workforce crisis.

I will also fight to expand paid family and medical leave

nationwide. Each of these elements is

critical to better supporting family caregivers.

--Joseph R. Biden, Jr., A Proclamation on National Family Caregivers Month (Oct. 29, 2021)

It takes a

village + infrastructure, like job-protected leave and healthcare coverage, to

support family care partners.

· Effective Jan. 1, 2022, California Family Rights Act (AB 1033) expanded to grant eligible employees up to 12 weeks of job-protected leave to care for parent-in-law with a serious medical condition.

· Effective Jan. 1, 2023, Parent Health Care Act (AB 570) will allow adult children to add their parents/step parents (who are not eligible for Medicare) as dependents to their individual health insurance coverage.

https://twitter.com/CaregiverAction/status/1457888929127014402

This year’s NFCM theme is #CaregiverAnd, which encourages family caregivers to “celebrate the passions and interests that enrich their lives.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns, many family caregivers were on their own without the usual respite supports from other relatives/neighbors/friends (as people formed their own pods/bubbles) and formal supports like home health/adult day centers/congregate care settings. Compared to non-caregivers during this pandemic, research found that family caregivers experienced higher rates of anxiety, depression and disturbed sleep; and reported less social interaction, more worries about finances and food, even after controlling for income and employment. Caregivers who fared the worst were female, young, lower-income, and providing care for people with cognitive disabilities (dementia) or behavioral/emotional problems.

According to UCLA study, Who Is Caring for the Caregivers? The Financial, Physical, and Mental Health Costs of Caregiving in California (Nov. 29, 2021):

·

In

2020, 1 in 4 California caregivers provided 20+ hours of care to a family

member/friend in a typical week, yet only 1 in 11 received payment for any of

the hours spent providing care

·

Majority

of caregivers in California are women (57.7%), middle age or ages 26-64 (67.5%)

and provide care to mainly older adults ages 65+(64.7%).

·

Nearly

half (44.4%) of California’s estimated 6.7 million adult caregivers reported

experiencing some level of financial stress in 2020 due to their role.

·

About

1 in 5 (20.9%) caregivers reported that caring for their relative/friend was

somewhat to extremely financially stressful.

·

1

in 7 caregivers (13.5%) reported a physical or mental health problem within the

past 12 months due to caregiving.

Aging boomers in later life have fewer family members to rely on for caregiving (due to never married, divorce, no kids, etc.). (China has recognized tradition of family caregivers, and “Confronted By Aging Population China Allows Couples To Have Three Children.”)

“I’m a single woman, so I say mom has me, but I don’t have a me.”—Lily Liu, who took “gap year” from her job to set-up infrastructure of care for her mom, featured in AARP documentary, Caregiving: The Circle of Love (2016)

(See Mission Local’s “For Mao survivors, the pandemic has been a cakewalk.” In 2015, Administration for Community Living awarded its first grant to develop “person-centered, trauma-informed” care for Holocaust survivors.)

Patti Davis wrote her handbook + memoir, Floating in the Deep End: How Caregivers Can See Beyond Alzheimer’s (2021), based on her caregiver support group, Beyond Alzheimer’s (started in 2011) and caring for her father Ronald Reagan who died in 2004. After her attempt to license Beyond Alzheimer's into “AA of caregiver support” fell through, she decided to write her book to share lessons, like addressing grief (“you’re well-served to inhabit and surrender to grief early on…grief is not biodegradable, it will wait and come find you…”), looking beyond disease to essence of person (“Alzheimer’s is stripping away of façade… my father was sweet, gentle person so it was easier”), educating about disease and acceptance to take on challenges like taking away car keys (avoid 86-year-old George Weller’s 20-second drive through farmer’s market in Santa Monica killing 10 people, and injuring many others.) She broadly viewed a caregiver as someone who shows up to provide support; her father received homecare from paid caregivers when he was “bedridden” during last three years of his 10-year illness.

“Kupuna edge”

“When you’re a caregiver … you’re the nurse, you’re the physician, you’re the lawyer, you’re the chauffeur, you’re the accountant. You play all of these different roles that most people go to school and get a degree for, and you are expected as the caregiver to become all of that overnight and as the disease progresses.”— Poki‘i Balaz, geriatric NP, “Our Kūpuna, Our Kuleana: Senior Care Crisis in Hawaiʻi,” Hawai’i Business (Feb. 4, 2020)

Growing up with kupuna (grandparents) in the same

household, family caregiving was reciprocal: my grandparents cared for me and

my siblings (while my parents worked outside of our home) until we became more

independent, and then we reciprocated as my grandparents with dementia became

more dependent on us for activities of daily living. This caregiver experience

was more like something we grew into as needs arose, rather than “overnight.”

And I suppose it helped that my grandparents had more than a single caregiver

playing different roles, and benefited from many family caregivers with

specialized roles including physician (though trained in OB-GYN; my cousin

didn’t become a geriatrician until after grandparents died), lawyer,

accountant, and we were all (non-degreed, but licensed) chauffeurs!

Last month, Hawaii Business magazine covered the role

of kupuna in caring for grand keiki in a series of articles about

Hawaii’s so-called kupuna edge:

· "Grandparents Help Hawai‘i Parents Get the Job Done: Grandmothers and grandfathers are storytellers, sources of wisdom, keepers of family legacies and teachers. But perhaps their most important role in Hawai‘i is to help working parents raise their keiki.”

· "Do’s and Don’ts of Using Grandparents for Child Care: Lessons learned from both grandparents and parents about navigating these relationships.”

· "Grandparents Are Great, But They Can’t Solve All of Hawai‘i’s Child Care Needs: Hawai‘i’s high cost of living often drives the need for grandparent-provided child care. But many grandparents can’t provide care because they are still working or live on the Mainland. Here’s what else is needed.” This article noted that grandparents who are the primary caregivers for their grandchildren tend to experience worse physical and mental health than those who provide occasional or no child care at all.

Kupuna might wish to exchange worse health for a stipend while serving in foster grandparent program and more low wage opportunities await them in proposed Caring Corps for older adults in charge of universal early childhood education?!

This month, the Advisory Council to Support Grandparents Raising Grandchildren (SGRC) released its Initial Report to Congress. Highlights:

· In USA, 2.7 million children are being

raised in the homes of grandparents.

· The child welfare system increasingly

relies on kin or grandfamilies to provide care for children, yet they are less

likely than non-related foster families to receive needed supports and

services.

This report also

provides recommendations that will inform development of the National Family

Caregiving Strategy.

As COVID-19

pandemic seemed to accelerate hospital discharge preference of patients to go

home rather than receive rehabilitation care from a skilled nursing facility

(SNF), some exciting Home- and Community-Based Services (HCBS) policy proposals:

· Choose Home Care Act of 2021 (S.2562/H.R. 5541) would increase access to health services at home by giving eligible Medicare beneficiaries the option to choose home-based extended care as an alternative to SNF care after being discharged from the hospital.

· Justice in Aging is advocating for change in federal Medicaid law to apply retroactive coverage of HCBS services after hospital discharge, just as Medicaid allows services to be covered up to 3 months for SNF.

Advance care planning

Geriatricians

are expert at managing syndromes that are associated with age (e.g., dementia)…

are good at deprescribing, looking at list of medications and possibility of

interactions…eliminating what’s not necessary… really useful if multiple

chronic illnesses… key to good care as we get older is constant, ongoing

communication with your doctor… about what you want, how aggressive you want,

that trade-off between things that might possibly prolong life versus

side-effects and quality of life.

--Jay Luxenberg, MD, On Lok Chief Medical Officer, “Do We Need New Doctors As We Age?” Not Born Yesterday podcast (Oct. 15, 2021)

UCSF geriatrician Dr. Anna Chodos presented on Advance Care Planning (ACP): how to make decisions based on context (emotions, needs, resources), personality, values, and experiences.

ACP includes medical and financial/legal considerations.

Wonder how many people attended this webinar? I asked all 4 questions! Answers:·

Even if elder orphan is

unable to name a surrogate, it is appropriate to document that person’s

preferences—even if “terrible system” for people who are not going to have an

advocate, POLST may or may not be useful.

· “Many of us deal with people who are really complex and seem to have a lot of wishes for what life is like now that don’t match up with what are some stated long-term goals like living forever, getting better…it’s a process we continue to revisit…most people do not like thinking about the hard stuff…Most people don’t get the point, they don’t understand what the heck we’re asking them to do…completing advance directive takes at least a half hour, if not an hour.”

· “Assuming they have a program where you can live forever,…what most religions promise people. No, I haven’t started referring people to Jehovah’s Witness programs, but I hope that was like a cheeky question…they’re plenty of religions that have very specific requirements for how people get healthcare.”

According to AARP, Hawaii has 157,000 family caregivers providing $2.1 billion value of u(n)paid care! AARP HI Pre-Crisis Planning for Dementia featured elder law attorney Laurie Adamshick, who shared her family caregiving experience.

For solo agers (“elder orphan” without family caregiver), she advised hiring a professional fiduciary.

Chinese American Coalition for Compassionate Care (CACCC) and AACI hosted Chinese American Cultural Challenges at End of Life (EOL) presented by Esther Luo, MD, Kaiser Permanente palliative care specialist. According to Pew Research, Asians are the fastest growing racial/ethnic group in USA, and Chinese are the largest Asian origin group making up 24% of this group.

According to California Health Care Foundation’s Help Wanted: Californians’ Views and Experiences of Serious Illness and End-of-Life Care

(2019), majority of Californians at EOL do not want to “burden” family, want

to die at home, prefer “natural death” and do not want to suffer pain.

Compared to whites, Chinese

Americans receive more aggressive EOL care including invasive mechanical ventilation when hospitalized and deaths in ICU so

fewer die at home.

Few Chinese Americans enroll in hospice due to cultural challenges, including finding providers with cultural sensitivity (honor family-based v. individual decision-making) and language fluency. About 25% of Chinese Americans live in traditional multigenerational household; modern Chinese family structure is more like the family depicted in The Farewell (2019) film: adult children live separately from aging parents, varying acculturation (immigrant with limited English so gaps in communication with USA-born children/grandchildren), working adult children may have limited time for direct care, so more common to hire or place elder in care home.

Traditional filial duties might include nondisclosure to protect psychological well-being of elderly parent; advocate for aggressive treatment to prolong life; pressure to perform duties to avoid disapproval of community (save “face”); provision of food at EOL as cultural obligation to demonstrate love and care.

“New” approach to filial piety involves ACP with parents initiating discussion and decision-making in context of not being burden to family, and reframing love/care by honoring elders’ wishes.

Good death is part of 5 blessings, along with

love of virtue, longevity, wealth, health. To traditional Chinese, components

of good death are defined by one’s accomplishments of familial responsibility;

“natural death” in old age; minimal suffering and free from pain; and maintaining

good family relationships.

Dr. Luo recommended indirect communication preferred

when discussing EOL: use another person’s EOL experience; frame discussion as

standard question and part of routine

care; acknowledge cultural taboos and ask for permission (e.g., some may fear

invoking “bad luck” if they discuss death, or talking about death might invite

death to come sooner); use provider’s own experience as example.

Last month, I completed mandatory First Aid/CPR/AED training. During COVID-19 pandemic to prevent contamination, rescuers place material over the victim’s mouth and nose. This mannequin did not look like Resusci Anne.

During COVID-19 pandemic, call 911 and stick to compression-only CPR: check for response, check for breathing (look; careful about exposure if you listen and feel), then start chest compressions 100-120 beats per minute to the rhythm of BeeGees’ Stayin’ Alive! Use AED defibrillator.

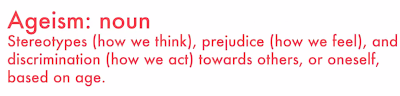

Ageism in healthcare

Kaiser Health News’ Navigating Aging columnist Judy Graham moderated stimulating 90-minute panel discussion, Confronting Ageism in Healthcare: A Conversation for Patients, Caregivers and Clinicians. What we can do:

· Louise Aronson, MD, UCSF geriatrician and author of Elderhood: suggested how to communicate with provider to get your needs met—e.g., “I feel that I’m not getting attention my symptoms warrant (use “I” statement), and I came to you because of your reputation as a good doctor” (compliment!). And she incited us to “make a ton of noise and don’t shut up until things change…that’s how other social change movements succeed, own it, be noisy. Let’s do it!” She added Essential Caregiver Bill (HR 3733) in Zoom chat box.

· Michael Wasserman, MD, geriatrician and immediate past president of California Association of Long-Term Care Medicine (CALTCM): encouraged us to “speak truth to power”; called out federal government spending $10 billion a year subsidizing graduate medical education, but failing to train doctors to care for Medicare beneficiaries; the failure to develop policies focused on older adults due to the lack of geriatric expertise among policymakers (notably, failure of Biden administration to appoint gerontology expert to COVID-19 task force)—“honestly, the federal government didn’t listen, and now we have over half a million deaths amongst older adults from COVID and close to 200,000 of them from nursing homes…honestly, the policymakers don’t seem to care.” (The lack of gerontology expertise proved fatal in nursing homes that cut off family visits since March 2020 through Nov. 12, 2021 when finally CMS lifted visitor restrictions in nursing homes.)

·

Rebecca

Elon, MD, geriatrician and family caregiver (see “Aiding Her Dying Husband, a Geriatrician Learns the Emotional and Physical Toll of Caregiving”): recommended starting local and with

groups for a louder voice!

·

Javette

Orgain, MD, family physician and medical director for Longevity Health Plan of

Illinois: called for intergenerational living, closing technology gap, increased

funding of home-based care and improving nursing homes!

· Jesse Mauer, JD, Executive Director of Maine Council on Aging, which promotes Anti-Ageism Pledge: advocated to include age in every DEI (diversity, equity, inclusion) conversation to “help us move collectively together”! (Check out recorded 2021 Wisdom Summit: Embracing a New Normal, Bouncing Forward to Build an Age-Positive Maine.)

Despite anti-ageism

guide to language tip, “do not use ‘elderly’ as a reference to a group,”

transcript showed use of “elderly” in reference to a group almost

interchangeable with “older adults” in same sentence:

·

Dr.

Orgain said she “began care for older adults prior to becoming a physician, so

I had some experience there that fostered my love for the care of the elderly.”

·

Judy

Graham asked Dr. Orgain about “the lack of resources and what that says about

how we approach our elderly population and what it means for those older

adults.”

Maine’s

Anti-Ageism Pledge includes “call attention to ageist language,” which depends

foremost on what “the person wants to be described” as an equity consideration,

and otherwise “refer to people over

60 as older people instead of seniors or the elderly.”

[Similarly,

University of Iowa researchers Clarissa A. Shaw, PhD and Jean K. Gordon, PhD,

advocate for an individualized, person-centered approach to communication

accommodation based on person’s preferences and needs, not stereotypes of aging;

for example, not all older adults find “elderspeak” (which arises when caregivers

take on parental role) to be patronizing, particularly when it facilitates

comprehension (e.g., slow speech, simplified sentence, long pause, loud voice, repetition,

etc.). Otherwise, elderspeak is harmful!]

Judy Graham summarized efforts to address ageism in healthcare: remove old age as a cause and symptom of disease; identify ageist beliefs and language (Frameworks Institute); tackle ageism at grassroots level (Changing the Narrative); require geriatrics education for medical students; include older adults in clinical trials; bring in geriatrics expertise; build age-friendly health system.

Joined screening of 16-minute video premiere of Changing the Narrative’s Antidotes for Ageism: A Brief Guide to Creating Inclusive Care in an Ageist Society, followed by discussion with talking heads from video. Take-aways:

· Our age does not define us (so stop attributing everything to “growing older”); instead, age-inclusive healthcare starts with caring for people as individuals because “every person is living a unique human experience.”

·

“If you are receiving care: Talk to your

provider. Ask questions. Your goals shape the course of your healthcare.

Clarify what you value to avoid under- or over-treatment. Advocate beyond

conversations with healthcare providers.

Seek care providers that truly listen to you, and support your vision

for your health.” (Can this be done in typical 15- to 20-minute visit?!)

·

“If you are a healthcare professional:

Active listening and letting patients guide care.”

Geriatrician Jeff Wallace, MD, advised: “Get to know the patient, whether they’re age 20 or age 80, and get the background, and that’s the fun part in many ways, to learn about your patient to start…the therapeutic relationship with a patient starts with respect. You have to respect them, and they have to respect you…doctors should be interrupted more often…it’s okay to say, ‘let’s just timeout, and I really want you to focus on this.’”

Consultant Carolyn Love said she understood that doctors and nurses are medical experts, but patients are experts of their own body so providers need to listen.

Gilliane Lee, recent graduate of occupational therapy (OT), talked about shift to focus on safety as well as quality of life for older adults, and responded to following Q&A:

Q:

What are some things that can be done to encourage more people to work with

older adults?

A:

“Bring them to assisted living facilities (ALF) and getting that exposure so

that they can understand that there is such a need for providing care.”

Oy vey, will exposure to ALF for understanding “need for providing care” translate to encouraging more people to work with older adults? Possible to deter people from working in ALF setting like Brookdale, the nation’s largest senior living provider and target of federal lawsuit on behalf of 83 families alleging elder neglect and financial abuse, as well as lawsuit by California Attorney General?! As a graduate gerontology student, I watched Life and Death in Assisted Living (2013), PBS Frontline documentary that featured my instructor Pat McGinnis, founder and Executive Director of California Advocates for Nursing Home Reform; that horror show convinced me to stay away from for-profit ALF!

“Too

many assisted living centers, care centers, and nursing homes are places I

would never allow a loved one to enter. Most wouldn’t either if they knew what

the facilities were really like. However, families who schedule facility tours

and interviews when considering placing a parent or grandparent, do not see

that side…Families must learn to get behind the scenes in order to see the truth.”

--Linda L. Schlenker, OTR, author of Aging in America: A Wake-Up Call and

Call to Action for Seniors and Those Who Love and Serve Them (2008),

calling out non-profit Mayo Clinic and St. Anne’s Home, Little Sisters of the

Poor (SF) as exceptional

Been there,

done that with my own stint working in ALF (non-profit, of course)! People who

get behind the scenes by working in ALF see truth of “need for providing care”:

understaffing, lack of staff trained in gerontology and experienced in working

with older adults, low morale, high turnover, etc. Residents who wait too long

for assistance end up trying to manage on their own, resulting in falls,

bedsores, medication errors, other neglect.

Exposure to

older adults segregated in ALF seems to reinforce warehousing people based on old

age/disability. More encouraging to meet older people where they are in a

variety of settings, listen and let their complexity grow on you until you

decide this could be an interesting way to earn a living 😉!

Ageism in media

Ageism isn’t even recognized in Pew Research’s list of 15 biggest problems facing the nation; in contrast, racism and sexism make the list.

November 2021

issue of The Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences featured several articles

about media coverage of aging and ageism.

In Aging Narratives Over 210 Years (1810-2019), Reuben Ng, PhD, found aging narratives

in newspapers, magazines and nonfiction books have become more “negative” over

210 years, from “uplifting narratives of heroism and kinship” in the 1800s to

“darker tones of illness, death, and burden” in the 1900s as older adults came to be viewed as dominant occupants of almshouses and described as deserted by their

children and too infirm to work. Contributing to this ageism were the

diminishing status of older adults, loss of warmth, loss of competence, social

ostracism, and medicalization of aging. Defying this trend was fiction, which

provided “positive” portrayals of older adults through romantic courtship and

war heroism.

In Ageism in COVID-Related Newspaper Coverage: The First Month of the Pandemic, researchers analyzed 287 articles concerning older adults and COVID-19, published between March 11 and April 10, 2020, in four major U.S. newspapers (USA Today, The NY Times, LA Times, The WaPo), the term “ageism” appeared only five times and only in The NY Times opinion pieces, suggesting that journalists were not calling out ageism.

This failure to call out or name ageism seems to normalize ageism so it’s not viewed as the problem it is with harmful impacts.

Journalists

continue to confuse assisted living and nursing home, needing to issue

corrections like “This story has been corrected to refer to Brookdale as an

assisted living and memory care center instead of a nursing home.” In “The Forgotten Nursing Home Tragedy” (NY Times,

Nov. 4, 2021), journalist stated “Nurses were routinely working at several

elder-care facilities at once”—more likely the reality is lower-paid certified nursing assistants (CNA) who have closer hands-on contact with residents (assisting

with toileting, bathing, dressing, feeding, etc.) work at multiple nursing homes? Important to understand differences: ALF v. SNF, CNA v. nurse.

Wish more journalists would follow reporter Laura Wenus’ advice to consult someone with expertise in the field because “elder care and nursing care is a complex industry” so it helps to turn to a second pair of eyes to ensure “using the right terms and describing the relevant systems correctly.”

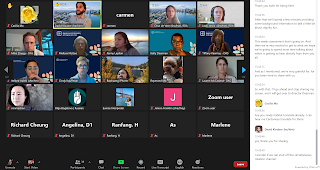

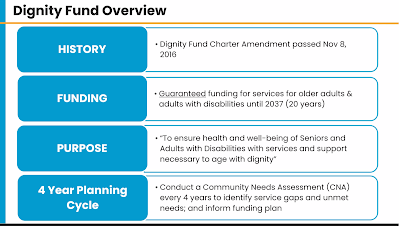

SF Dept. of Disability & Aging Services (DAS) hosted SF Dignity Fund Community Needs Forum (“What do older adults & adults with disabilities living in San Francisco need?). This took place on day after holiday weekend, 39 showed up on Zoom, mostly DAS staff; service providers who participated talked about workforce challenges like finding social workers who are Cantonese bilingual and who are familiar with African American culture.

I completed 36-item SF Dignity Fund Community Needs Assessment survey, commenting on need for gerontology training in workforce development to better serve diverse older adults, like designing a more age-friendly survey! Wonder how many older adults/people with disabilities had stamina to actually answer all survey items: e.g., 5-item Likert scales for #6 Please rate your agreement with the following (19) statements about your needs; #17 Please rate your agreement with the following (15) statements about any barriers you have experienced when trying to participate in services. By the time I got to survey's demographic information section, I just wanted to get over ordeal so quickly selected "Decline to answer"!

Caring for an older loved one is impossibly difficult. Manchin and GOP just made sure it will stay that way

ReplyDeleteDave Iverson

Dec. 20, 2021

…I’d moved in with my 95-year-old mom in 2007, when she could no longer live alone. I was a 59-year-old broadcast journalist at the time…

My life was full, but flexible. It just made sense, I thought, to move in and help.

…I didn’t know how exhausted I’d become or how angry I would get. I didn’t know the Parkinson’s disease I’d recently been diagnosed with would prove less challenging than being a caregiver. I didn’t know that I’d be tested in ways I’d never imagined or rewarded in ways I’d never dreamed.

It’s often said that no one is fully prepared to become a parent, but I think only a paltry few are prepared to care for a parent.

…That’s why the decision Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin of West Virginia and 50 Republican senators have made to reject President Biden’s Build Back Better plan, and the eldercare funding it provided, is so disappointing, so short-sighted and ultimately so hurtful. That legislation would have helped millions of needy older Americans receive critical home-based services.

Most people think Medicare pays for long-term eldercare. It does not. Medicaid, which assists lower-income Americans, sometimes provides coverage, but largely at long-term care facilities. That’s not a reliable plan, not when COVID-19 has already killed at least 184,000 residents and staff of those institutions.

Most people who want to care for an aging parent or spouse at home aren’t as lucky as I was.

…I could borrow against the house to hire skilled caregivers while I was at work; I just had to cover nights and weekends. Plus, I could pay them what they were worth.

But even a dozen years ago, that amount of care cost about $4,500 a month, a sum that would eventually triple by the time my mom needed 24/7 care.

I was lucky. But should luck determine who gets loving care?

That why we must still find a way to help not only those who desperately need care, but also those who provide it.

…When I was caring for my mom, I was accompanied by remarkable women, all immigrant Americans, whose constancy, skill and gentle care reminded me of the tender miracle a simple touch can provide.

Until we were under the same roof, I hadn’t understood how incredibly demanding that work can be, nor did I fully appreciate the challenges you face when you have to work two jobs to make ends meet.

…My care partners brought to America a deep cultural understanding that caring for the old is part of life’s bargain.

The next time you hear someone say that those who come to this country need to possess special skills, ask them to think a little more about which skills those are and why they’re needed more than others.

My mom lived for another full decade after I moved in before passing away at the age of 105.

…Being able to ensure your loved ones are treated with tenderness, dignity and respect is not something that should depend on luck, good fortune or politics. It should depend on the kind of nation we want the U.S. to be, a nation that honors both those who need care and those who provide it.

Dave Iverson is…author of “Winter Stars: An Elderly Mother, an Aging Son and Life’s Final Journey,” to be published March 22.

https://www.sfchronicle.com/opinion/openforum/article/Caring-for-an-older-loved-one-is-impossibly-16717746.php

A New Paradigm Is Needed: Top Experts Question the Value of Advance Care Planning

ReplyDeleteBy Judith Graham

JANUARY 6, 2022

…“Decades of research demonstrate advance care planning doesn’t work. We need a new paradigm,” said Dr. R. Sean Morrison, chair of geriatrics and palliative medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York and a co-author of a recent opinion piece advancing this argument in JAMA.

“…increasing the prevalence of advance care planning, but the evidence is clear: It doesn’t achieve the results that we hoped it would,” said Dr. Diane Meier, founder of the Center to Advance Palliative Care, a professor at Mount Sinai and co-author of the opinion piece. Notably, advance care planning has not been shown to ensure that people receive care consistent with their stated preferences — a major objective.

…The reasons are varied and documented in dozens of research studies: People’s preferences change as their health status shifts; forms offer vague and sometimes conflicting goals for end-of-life care; families, surrogates and clinicians often disagree with a patient’s stated preferences; documents aren’t readily available when decisions need to be made; and services that could support a patient’s wishes — such as receiving treatment at home — simply aren’t available.

But this critique of advance care planning is highly controversial and has received considerable pushback.

Advance care planning has evolved significantly in the past decade and the focus today is on conversations between patients and clinicians about patients’ goals and values, not about completing documents, said Dr. Rebecca Sudore, a professor of geriatrics and director of the Innovation and Implementation Center in Aging and Palliative Care at the University of California-San Francisco…

Also, anticipating what people want at the end of their lives is no longer the primary objective. Instead, helping people make complicated decisions when they become seriously ill has become an increasingly important priority.

…Congress passed the Patient Self-Determination Act, which requires hospitals, nursing homes, home health agencies, health maintenance organizations and hospices to ask whether a person has a written “advance directive” and, if so, to follow those directives to the extent possible… But too often this became a “check-box” exercise, unaccompanied by in-depth discussions about a patient’s prognosis, the ways that future medical decisions might affect a patient’s quality of life, and without a realistic plan for implementing a patient’s wishes, said Meier, of Mount Sinai.

She noted that only 37% of adults have completed written advance directives — in her view, a sign of uncertainty about their value.

Other problems can compromise the usefulness of these documents. A patient’s preferences may be inconsistent or difficult to apply in real-life situations, leaving medical providers without clear guidance, said Dr. Scott Halpern, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine who studies end-of-life and palliative care.

…“Rather than asking patients to make decisions about hypothetical scenarios in the future, we should be focused on helping them make difficult decisions in the moment,” when actual medical circumstances require attention, said Morrison, of Mount Sinai.

Also, determining when the end of life is at hand and when treatment might postpone that eventuality can be difficult…early in the pandemic when older adults with covid-19 would go to emergency rooms and medical providers would implement their advance directives (for instance, no CPR or mechanical ventilation) because of an assumption that the virus was “universally fatal” to seniors…

https://khn.org/news/article/advance-care-planning-palliative-care-experts-paradigm-shift/

When Faced With Death, People Often Change Their Minds

ReplyDeleteJan. 3, 2022

By Daniela J. Lamas

Dr. Lamas, a contributing Opinion writer, is a pulmonary and critical-care physician at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

…Since the Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990 went into effect, advance care planning — which encourages all adults, even those in good health, to choose a surrogate to make medical decisions and to draw up an advance directive — has been promoted as the way to make sure that people receive the care they want at the end of their life.

But this well-intentioned effort has not worked as promised. In a recent commentary published in The Journal of the American Medical Association, Dr. R. Sean Morrison, a palliative care specialist, and colleagues wrote that despite decades of research on advance care planning, there are scant data to show that it accomplishes its goals. A 2020 review of more than 60 high-quality recent studies on advance care planning found no impact on whether patients received the care they wanted, or how they rated the quality of their lives afterward.

When doctors talk to patients about advance directives, they implicitly promise that the directives will help patients get the care they want and unburden their loved ones, Dr. Morrison told me. “And the reality is that we’ve been pushing a myth,” he said.

I once thought that the only barriers to effective advance care planning were practical. Not all people are aware of how to write such a directive, and even if they are, the document is not always uploaded into patients’ medical records or is easily retrievable.

But the bigger obstacle, and what has increasingly troubled me working in the intensive care unit, is the difficulty of asking people to make decisions about future scenarios.

Humans have an amazing capacity to adapt to illness or disease. From the vantage point of youth or good health, it is easy for people to say that they would rather die than live with significant limitations, pain or dependence on others.

But people evolve in ways they cannot expect. This is why some survivors of catastrophic accidents, such as spinal cord injuries leading to complete paralysis, nevertheless come to rate their quality of life as good — even if they never would have imagined being able to do so before the accident. As a result, what people are willing to go through to extend their life might change depending on the context. Advance directives written at one point in time about hypothetical scenarios cannot capture what someone actually wants at every point in the future.

A key goal of advance care planning is to free family members from the burdens of making decisions, yet these conversations can paradoxically leave relatives with even more conflict. A loved one may have said years ago that she would want “everything” done. Was she imagining weeks on a ventilator and continuous dialysis without a reasonable hope for recovery?

…there is a better way.

We all should choose a health care proxy, someone who knows us well and whom we would trust to make hard decisions on our behalf, and document that choice in writing…This should not be done in order to make statements about medical treatments that are in any way binding, but to practice what it is like to say those words and experience the complicated feelings that arise when these topics are at hand.

Most important, we need to shift the focus from talking to healthy people about what would happen should they stop breathing during a routine procedure, and toward improving conversations with people who are already seriously ill. All patients for whom these decisions are no longer hypothetical should have a documented conversation with their doctor that focuses less on their thoughts about specific medical interventions and more on their understanding of their prognosis, what is important to them and what gives their lives meaning…

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/03/opinion/advance-directives-death.html

People Over 80 Are Still Taking Care of Their Parents and Partners

ReplyDeleteAs we live longer, more people are caring for loved ones well into their retirement years

By Clare Ansberry, The Wall Street Journal

Feb. 9, 2022

The U.S. population is aging, and so are caregivers…

The increasing number of caregivers 65 and older is adding a layer of fragility to the nation’s already strained family caregiving system, long the backbone of long-term care. Having a loved one around in old age is a blessing for many, and caring for a loved one provides a sense of purpose. But the duties are upending what many had expected from their retirement years.

An estimated 19% of the nation’s 53 million unpaid family caregivers are 65 and older, up from 13% in 2004. Caregivers in advanced age—75 and older—now represent 7% of caregivers, according to the 2020 Caregiving in the U.S. report by the National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP.

Older caregivers are likely to be dealing with their own health needs. They might not be in the “sandwich” stage of life, juggling a job and teenagers, but may have arthritis and a bad hip, live on fixed income and live 500 miles away from the person whose care they are responsible for.

“People need layers of support and backup plans,” especially when caregivers are older, says Louise Aronson, geriatrician and professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco. A few years ago, she had a patient, a mother in her 90s, who outlived her caregiving daughter who had a stroke in her late 60s.

Older caregivers can benefit from the feeling of well-being in caring for others, but the physical demands of tasks, such as helping an even older loved one get out of chairs or into beds, also take a toll. Constant worry and lack of sleep can add up, too…

About 10% of adults aged 60 to 69 whose parents are alive act as their caregivers, although many never expected to assume a mom’s or dad’s care in their retirement…

https://www.wsj.com/articles/people-over-80-are-still-taking-care-of-their-parents-and-partners-11644415549

Pandemic-Fueled Shortages of Home Health Workers Strand Patients Without Necessary Care

ReplyDeleteBy Judith Graham

FEBRUARY 3, 2022

Frail older adults are finding it harder than ever to get paid help amid acute staff shortages at home health agencies.

Several trends are fueling the shortages: Hospitals and other employers are hiring away home health workers with better pay and benefits. Many aides have fallen ill or been exposed to covid-19 during the recent surge of omicron cases and must quarantine for a time. And staffers are burned out after working during the pandemic in difficult, anxiety-provoking circumstances.

The implications for older adults are dire. Some seniors who are ready for discharge are waiting in hospitals or rehabilitation centers for several days before home care services can be arranged. Some are returning home with less help than would be optimal. Some are experiencing cutbacks in services. And some simply can’t find care…

“We’re seeing increasing demand on adult protective services as a result of people with dementia not being able to get services,” said Ken Albert, president of Androscoggin Home Healthcare and Hospice in Maine and chair of the national home care association’s board. “The stress on families trying to navigate care for their loved ones is just incredible.”

…giving priority for care to people who are seriously compromised and live alone. People who can turn to family or friends are often getting fewer services, said C.J. Weaber, regional director of business development for Honor Health Network, which owns Angels on Call.

“Most clients don’t have backup,” she said.

This is especially true of older adults with serious chronic illnesses and paltry financial resources who are socially isolated — a group that’s “disproportionately affected” by the difficulties in accessing home health care, said Jason Falvey, an assistant professor of physical therapy and rehabilitation science at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

Many agencies are focusing on patients being discharged from hospitals and rehab facilities…acute needs, and agencies are paid more for serving this population under complicated Medicare reimbursement formulas.

…families are filling gaps in home care as best they can…

Despite growing needs for home care services, the vast majority of pandemic-related federal financial aid for health care has gone to hospitals and nursing homes, which are also having severe staffing problems. Yet all the parts of the health system that care for older adults are interconnected, with home care playing an essential role.

Abraham Brody, associate professor of nursing and medicine at New York University, explained these complex interconnections: When frail older patients can’t get adequate care at home, they can deteriorate and end up in the hospital. The hospital may have to keep older patients for several extra days if home care can’t be arranged upon discharge, putting people at risk of deteriorating physically or getting infections and making new admissions more difficult.

When paid home care or help from family or friends isn’t available, vulnerable older patients may be forced to go to nursing homes, even if they don’t want to. But many nursing homes don’t have enough staffers and can’t take new patients, so people are simply going without care.

Patients with terminal illnesses seeking hospice care are being caught up in these difficulties as well…

Before the pandemic, hospice agencies could usually guarantee a certain number of hours of help after evaluating a patient. “Now, they really are not able to guarantee anything on discharge,” said Jennifer DiBiase, palliative care social work manager at Mount Sinai Health System in New York City. “We really have to rely on the family for almost all hands-on care.”

https://khn.org/news/article/pandemic-fueled-home-health-care-shortages-strand-patients/

I'm Ashley, from Texas, USA. I had been in a relationship with a guy and we had unprotected sex for the first time and within a day I got a big bump on the crease of my thigh and vagina. After a few days it began to hurt more and more. I told him to take a picture of it for me, and it looked like open sores, like bugs were biting off my skin or something. So I went to the ER and they said genital herpes. I was soooo depressed. My boyfriend and I cried. He cried for me, but he had no idea he had it too. The next day, the same thing happens to him. At this point, we think I gave it to him because I was the first one to show the symptoms. The next phase I went through was depression. At this point, all I did was sleep and cry. I felt like my life was over. I knew I could never get married, I felt dirty, and worthless. I was depressed for about two months. I fought thoughts of suicide and it was a hassle to even carry out my daily tasks. So I started to wonder if there would be a remedy to this disease, which led me to going to visiting many hospitals, and nothing good came out from it, until I read a person’s testimony online that said that they were cured with the help of Dr Harry, of this disease that the world deems incurable and tears rolled down my face. That person's testimony sparked a hope in me that led me to contact Dr Harry. So he assured us that we are going to be alright, after meeting up with the necessary requirements, he sent us a parcel and gave us an instruction guide on how to use it, which we did, after 7 days of using the medication, the herpes was totally cured. So my boyfriend and I went and got tested for every STD in the book and every single test came back NEGATIVE, we also went back to the hospital, and it was confirmed NEGATIVE. I am posting my testimony to help someone out there suffering from this disease. Do not hesitate to contact Dr. Harry via e-mail: drharryherbs@gmail.com or call him or whatsapp on +2348142350014

ReplyDeletewebsite: ?

HE ALSO HAS CURE TO THE FOLLOWING DISEASE:

HPV

GENITAL HERPES

TRICHOMONIASIS

CHLAMYDIA

HIV

GONORRHEA

HBV

AUTISM

DIABETES TYPE 1&2

SYPHILIS

we'll be glad to hear your healing story